Always wear a vest. That was the motto of my Great Aunt Louie – we assumed she didn’t mean exclusively a vest, but she always fell asleep before we could extract further insight. Despite such venerable wisdom in the family, I have successfully caught my first cold of the year. But this time the result has not just been misery, but some mystery too.

With an aching head and heavy limbs, you reach for a tissue and blow your nose – but, why is it green? It seems an appropriate, if disgusting, colour choice and one which I’d always blamed squarely on “bacteria”. They’re always depicted as green monsters in bleach adverts, and now they’ve apparently relocated from the toilet to my nasal passages. Great.

Yet this is the complete opposite of the truth. It’s not the nasty invaders that are turning my mucus green, it’s actually my own immune system operating with all-hands-on-deck. When you go to inspect your latest nasal offerings, you’re looking directly at the colour of an enzyme – myeloperoxidase – one of your body’s best molecular weapons in the fight for your health.

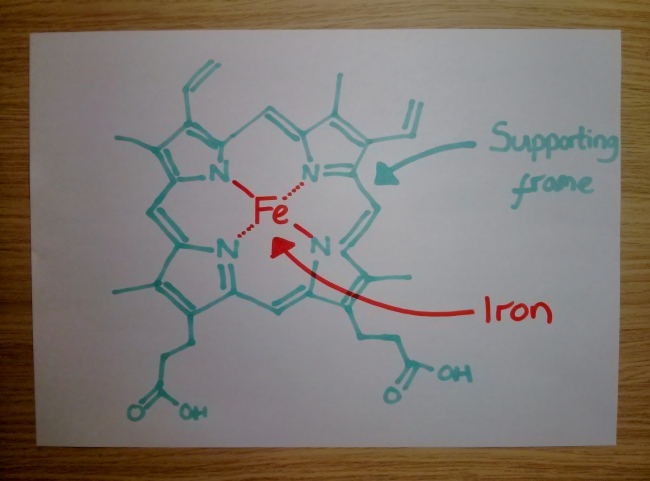

The colour was so striking that the enzyme was originally called verdoperoxidase when it was discovered. At its very core, this enzyme carries a haem molecule – a specialised building block made up of an iron atom carefully mounted into a supporting frame. Your body uses these haem molecules elsewhere too – they allow your blood to carry oxygen, and give red blood cells their characteristic crimson shade.

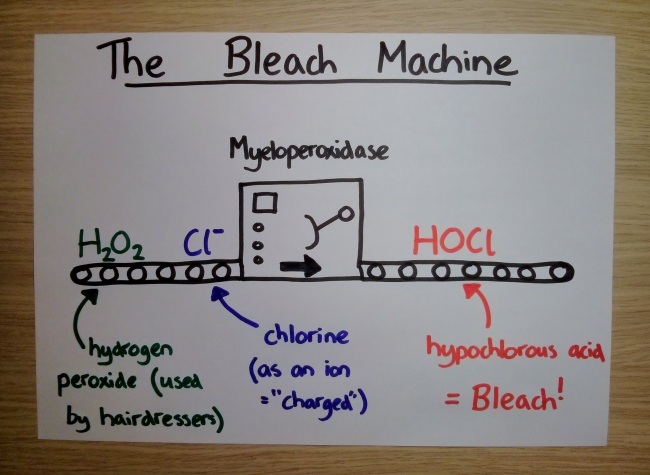

So why is this haem green, rather than red? Well, the potential horror of red mucus is avoided thanks to the way this particular enzyme grips its haem. Much like a stress ball in an overworked executive’s fist, the haem is slightly squeezed, which dramatically alters both its colour and, more importantly, what it can do. This unusual molecular grasp transforms the power of the haem – now, instead of binding oxygen it becomes a powerful bleach-producing factory.

And yes, bleach means bleach – hypochlorous acid – the same chemical that forms the basis for toilet cleaner and swimming pool disinfectant. Deploying such a potent force in your nose requires skill – bleach deals out damage indiscriminately, so friendly-fire is a major risk. To manage it effectively, the enzyme is made in a specific type of white blood cell, called a neutrophil. These are the heavyweights of the immune system, tasked with hunting down invaders and consuming them whole, PacMan-style.

Researchers in Germany have captured some fantastic (and terrifying) videos of a neutrophil mercilessly stalking the bad guys, before engulfing them whole – these cells are truly voracious. You do not want to make an enemy of a neutrophil. It will find you, and it will kill you.

Once captured, the neutrophil proceeds to douse its captives with bleach manufactured by our recent acquaintance, myeloperoxidase. Doing this internally allows a degree of damage limitation, tantamount to a controlled explosion. Sadly though, much like Monty Python’s Mr Creosote, the neutrophils can’t keep consuming forever. Eventually they take a suicidal step, rupturing open and spewing their digested contents out into the warzone, ready for you to honk out of your nose and admire.

Yet even in its final moment, the neutrophil and its enzymes have one final blaze of glory. As it ruptures, the cell releases its DNA – all 1.85m of it (celestial coincidence: Bill Nye’s DNA genome = Bill Nye’s height, apparently). These long strands mesh together to form an impenetrable net which snares any nearby bugs, halting their progress. Along for the ride comes a flood of all the left over enzymes, which can seize the moment for one final “hurrah” against these immobilised captives. What’s left behind after the carnage is just a pile of green goo, hardly a fitting end for such a glorious battle.

So next time you blow your nose, don’t recoil, but rejoice in the war that’s being won right under your nose.

Great read Ben!

Didn’t know my body was so heroic. Thanks for the info.

I’m really glad you enjoyed it, and thanks for the encouragement! The next post will be in about a week’s time, so check back!

Thanks for the info, Ben! I promoted the news on my FB page. People are so interested in basic knowlegde like this. My curious self was happy too! 🙂

I’m really glad you enjoyed it, and thanks for sharing it with your friends!

I’ve rarely if ever seen my snot green. Usually white.

Hello!, very nice article. I enjoyed reading it. I could relate to your enthusiasm for science and I can say you enjoyed writing this post. I enjoy writing about science too, you can check out my blog at http://www.yodacloud.wordpress.com ..cheers!..and keep up the good work.